–From the Winston-Salem Journal, Lisa O’Donnell, Dec 2018.

A Bond of Song: Two men, one from New York and the other from the mountains of North Carolina, formed an enduring friendship that brought the ballad of Tom Dooley out of the hollers and onto mainstream radio

(mouse over or tap image above to pause slideshow and to read the caption)

In winter mornings in the 1920s, as cold seeped through the cracks of a log cabin deep in the mountains of Watauga County, a young boy woke to the smell of biscuits and frying meat and the quiet strains of his father plucking a handmade banjo and singing “Hang your head Tom Dooley/hang your head and cry/hang your head Tom Dooley/poor boy you’re bound to die.”

Decades later, a version of that murder ballad, sung widely in the mountains of Northwest North Carolina, found its way into the repertoire of three clean-cut kids from the San Francisco Bay Area, known as The Kingston Trio.

They buffed the song’s rough edges, adding buttery harmonies and spare accompaniment to the chilling tale of a gruesome murder, a hanging and a mysterious character named Grayson.

Young listeners, eager to move past “Tutti Frutti” and “Blue Suede Shoes,” went mad for the song, turning it into a nationwide sensation that sold millions while turning the Kingston Trio into music’s hottest group.

The song represented a seismic shift in the landscape of popular music, creating commercial possibilities for folk music, which had long been associated with unions, lefties and coffeehouses. Within a few weeks of hitting the No. 1 spot on Nov. 17, 1958, The Kingston Trio, dressed in their trademark striped shirts, holding acoustic instruments, were on TV singing “Tom Dooley” on the Kraft Music Hall with Milton Berle, the epitome of Middle America in the 1950s.

A common refrain among music historians is that The Kingston Trio’s “Tom Dooley” plucked folk music out of the coffeehouses and onto the radio. But the song’s impact is much deeper, according to Greil Marcus, a longtime music critic who has written extensively on Bob Dylan, Elvis Presley and rock music as a cultural force.

“The coffeehouses became even more full of singers than before and there were more folk festivals than before,” Marcus said. “By the time Joan Baez comes along in 1959, 1960, there’s a huge audience ready for this kind of music, and they’ve been made ready by ‘Tom Dooley’ and The Kingston Trio.”

Similar to other traditional folk songs, there exists dozens of variations of “Tom Dooley,” based on the 1868 hanging of Wilkes County native Tom Dula. The version The Kingston Trio made into a pop music game-changer can be traced to that cold cabin in Watauga County, and Frank Proffitt, the young boy who grew into a hardworking but perpetually impoverished farmer with a gift for singing and telling stories.

The version of “Tom Dooley” his family sang might well have died in the mountains around Pick Britches Valley if not for Frank Warner, an intrepid song collector from New York City with a heart for mountain people and their traditions.

Together, Frank Proffitt and Frank Warner were critical links in the chain that gave the world “Tom Dooley.”

This is a story of what they gave each other.

‘A feeling we have never lost’

Frank Warner wanted a dulcimer.

A Duke-educated executive with the Grand Central YMCA in New York City, Warner had settled with his wife, Anne, in Greenwich Village in the 1930s, surrounded by artists and intellectuals, including Carl Carmer, a best-selling writer whose book “Stars Fell on Alabama” had put a lens on the culture and character of Alabama.

This was a time when Depression-era photographers Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange traveled the forgotten corners of the country, taking pictures of tenant farmers, migrants and miners in ways that reflected their dignity.

“All of that had to have some influence, especially on someone who was devoted to social work,” said Warner’s son, Gerret Warner, a documentary filmmaker who lives in Chapel Hill.

Frank Warner was no Greenwich Village bohemian, performing songs in a suit and tie, as opposed to the workingman clothes of Woody Guthrie. To him, traditional songs were not political tools but cultural treasures.

Raised on an integrated street in Selma, Ala., Warner absorbed the music of his surroundings. Later, at Duke, he sang songs in a folklore class to help bring to life the lectures of Professor Frank C. Brown, a noted folklorist.

Influenced by Brown, Warner fell in love with traditional folk music, with its British and Irish-inflected melodies, and tales of jilted lovers, seafarers and ramblers.

Warner’s voice could transport listeners to lumber camps and lonesome hollers, said Alan Lomax, a musicologist who made early recordings of blues legends Muddy Waters and Guthrie.

“When Frank was preparing to sing, you would note the delight rising in him. You could see his eyes glowing with fun, the corners of his mouth twitching. He was remembering the person whole…. so that the original singer was there, presented through Frank,” Lomax wrote in the introduction to “Traditional American Folk Songs from the Anne & Frank Warner Collection” by Anne Warner.

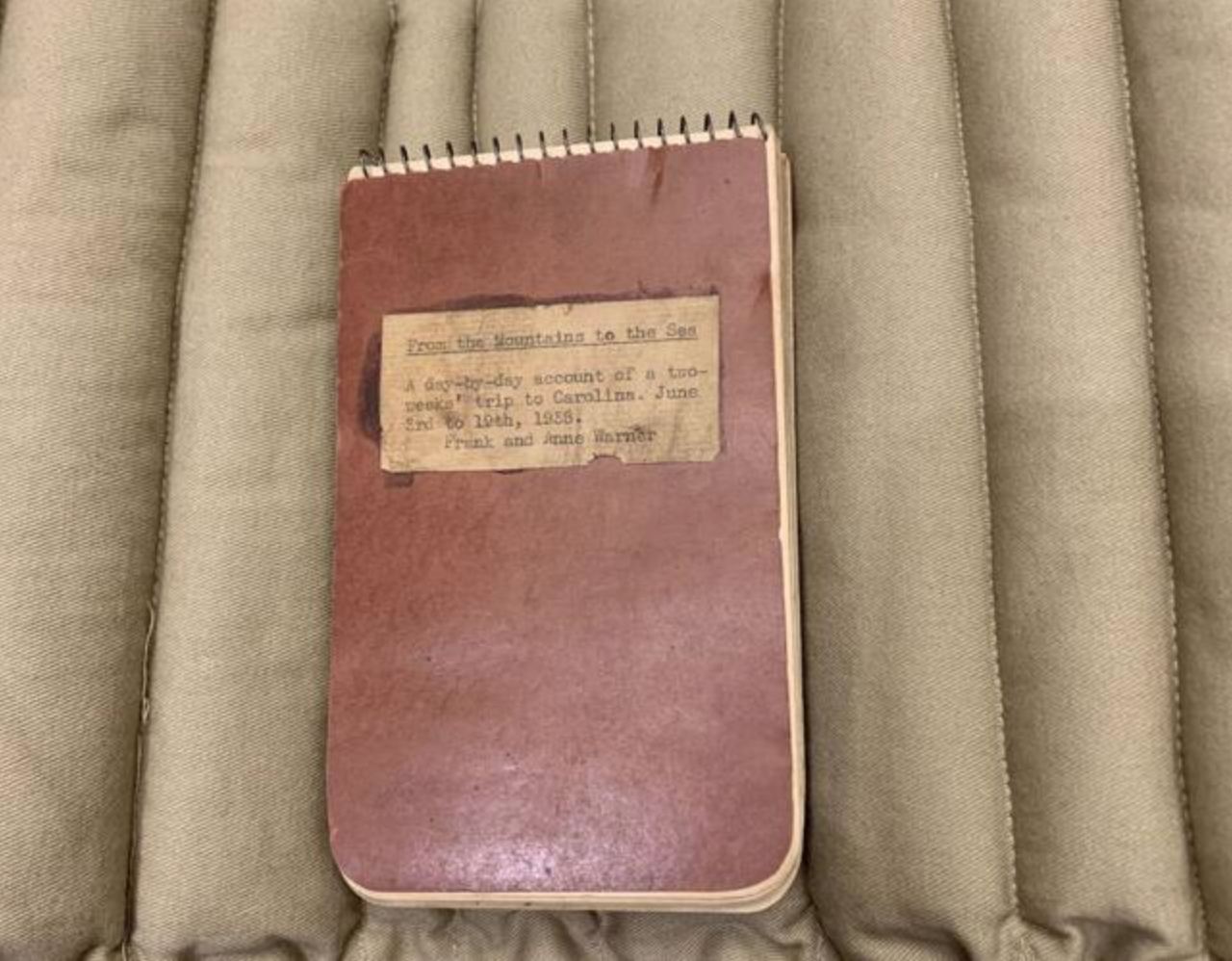

At a party one evening in New York in February 1938, Warner admired the dulcimer of a man who was recently back from Beech Mountain, a community in Avery County. The man explained that the dulcimer was handmade by Nathan Hicks, patriarch of a large family of musicians, storytellers and craftsmen.

Smitten by the instrument, Warner dashed off a letter to Hicks asking for his own dulcimer.

A response from Hicks soon arrived, requesting advanced payment. Postage, glue and nails were expensive; his wife was sick and there was barely enough wood to keep his 10 children warm.

The letter’s desperate tone moved the Warners, who collected blankets, clothing and food from their neighbors and friends to ship to Beech Mountain, the first in a string of care packages that would last for nearly 60 years. The Warners then decided to go one step further; they’d pick up the dulcimer themselves.

In June 1938, they made the long journey over two-lane highways and boulder-strewn wagon roads to Hicks’ house, their car loaded with more clothes and toys for the kids. Anne Warner noted the impoverished condition of the home’s interior, dominated by a big bed on which several people sat, and “rickety chairs with the seats falling out.”

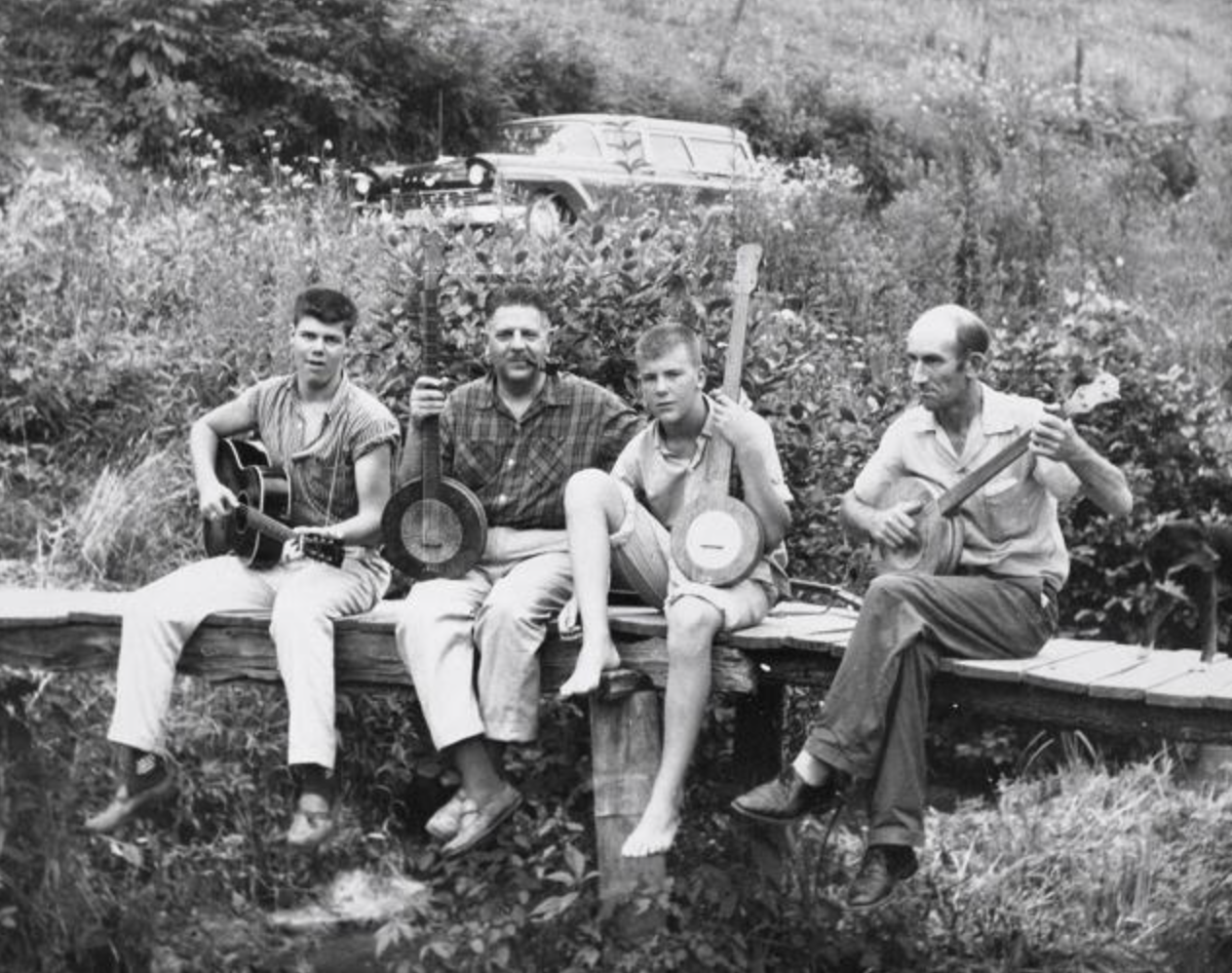

A crowd of 25 people, armed with guitars, banjos, dulcimers and fiddles inspected the Warners.

But whatever wariness each group felt toward the other quickly dissolved.

“Before long everybody was making music,” Anne Warner wrote in her book. “The sound, and the people that afternoon gave us a feeling we have never lost.”

Frank Warner was in his element, merrily singing, strumming and swapping songs, surrounded by men dressed in overalls and ties and women and children in their Sunday clothes. Anne, a secretary by profession, jotted down lyrics in shorthand as Frank won over the group with his good cheer.

Amid this joyful noise, Frank’s ear honed in on the singing and guitar playing of a wiry young man with an angular face, slick back hair and a faintly receding hairline. He had walked eight miles from his home in Pick Britches Valley to play music for the visitors from New York City.

His name was Frank Proffitt, and though naturally shy, he worked up the nerve to play a few songs handed down from his family.

One of them was “Tom Dooley.”

“It was a day,” Anne Warner wrote, “that changed our lives and his.”

As the Piney Knot Burns

Anne Warner once observed that life in Beech Mountain in 1938 had changed little from the 18th century. Electricity, running water, paved roads and other modern amenities had not reached North Carolina’s isolated High Country. Families subsisted on what they could grow in the rugged terrain. In lean times, that could mean cabbage and potatoes for weeks at a time. The beauty of the mountains and making music with friends and family softened such hardships.

Proffitt was born in such an environment, into a musical family that knew two of the characters in the “Tom Dooley” story — Dula himself and Laura Foster, the woman he stabbed with a knife. Dula was a Confederate soldier who, after returning from the Civil War, was convicted and hanged for killing Foster, his lover. Some have concluded that Dula was innocent of the crime but took the fall for the real killer, Ann Melton.

The tale was soon set to music, not surprising in a region of the country filled with storytellers and musicians.

Of his childhood, Proffitt reflected in one of his many letters: “Dad would hang the banjer around his neck, (take) a rifle and lantern and we would go to see the folks. As they gathered around the fireplace with a piney knot burning, us younguns would get a place down on the floor and listen to Tom Dooly and other songs being played.”

Though he dropped out of school in the sixth grade to help the family raise wintergreen and other crops, Proffitt had a curious mind and a boundless imagination.

“Let me tell you something about my dad,” Ed Proffitt said one day from his den in Vilas, about 10 miles northwest of Boone. “When us kids brought our books home, he read every one, geography, history, science, anything. He thoroughly studied them. You’d find them in his bedroom. He sought out that stuff.”

Early in their friendship, Proffitt would send Warner the handwritten lyrics to old songs in exchange for Life magazines. “I have always been interested in other countries and the way people live, and Life takes me right there,” Proffitt wrote in pencil on loose-leaf paper in 1941.

Proffitt, his wife, Bessie (Nathan Hicks’ daughter), and their children lived in a tiny cabin on a hillside not far from the Tennessee line. Tobacco was his main crop, but he took jobs as they came — clearing land, digging ditches, working in a spark plug factory in Toledo, Ohio, and for the Tennessee Valley Authority in Oak Ridge, Tenn.

He was thin but strong, his arms ropy from years of hard labor.

Ed Proffitt recalled seeing his dad walk straight up a hillside, one shoulder balancing a 75-pound bag of fertilizer, one arm wrapped around a second bag.

At some point, perhaps exhausted from feeding a family that had grown to six children, Proffitt stopped playing music, at least around the house. Ed Proffitt didn’t even know his father played an instrument, until 1958, the year the music world was abuzz with a new song, “Tom Dooley.”

Ed Proffitt, who was 9 years old when the record came out, remembered that around that time, his dad retreated to his workshop to build a banjo.

“I was laying on the couch late,” Ed Proffitt said, “and I heard the music.”

A mountain troubadour in the world

“Dec. 31, 1958

Dear Frank:

It looks like I am going to have to come down your way in January … You have surely heard that group of fellows singing Tom Dooley on a record over the radio and know that the record has become a hit. I have been singing that song ever since you taught it to me in 1939, 1940 and these fellows use the tune and words exactly as they have heard me sing it.”

Hearing The Kingston Trio sing “Tom Dooley” without crediting him or Proffitt knocked Warner for a loop. He fired off a letter to Proffitt, letting him know that he was considering challenging the Trio’s claim to the song.

Proffitt quickly responded:

“When I heard Tom Dooly I knew that it was surly from your collection. But I thought that you had sponsered it.”

The two made plans to meet in Boone to discuss next steps.

Warner was justifiably concerned about the copyright to “Tom Dooley,” which The Kingston Trio thought was public domain.

He had another concern as well — losing the trust of Proffitt, who had become a friend.

After their trip to Beech Mountain in 1938, the Warners returned to the area many times, including a trip in 1941 to record Proffitt singing “Tom Dooley” and other songs on a new battery-powered recorder made especially for them.

During these trips, Frank Warner grew especially close to Proffitt, convincing him that mountain songs and traditions held value. He also assured Proffitt that he had no intention of cashing in on his culture.

Warner did, however, want people to hear this music. He seemed particularly fond of “Tom Dooley,” with its dramatic lyrics, hummable melody and sing-a-long refrain, talking about it in lectures and performing it in his concerts, including a show at New York’s Carnegie Hall in front of 4,000 people.

Warner also sang the song to Alan Lomax, the country’s preeminent musicologist, who included it in his 1947 book, “Folk Song USA.” Warner made a few changes to the version he heard from Proffitt, paring down the lyrics and slowing down the tempo. The song began its slow circulation in music circles across the country, appearing in more song books and on records, including Warner’s 1953 Elektra album, “Frank Warner Sings American Folk Songs and Ballads.”

Accounts vary on how The Kingston Trio first heard the song. The most common story is that they overheard a man singing it one day in 1957 during an audition at the Purple Onion, a San Francisco club where the Trio frequently played. They liked the song, found the lyrics and recorded it for their self-titled debut album the following year.

Bob Shane, the only living member of The Kingston Trio, told British music journalist Paul Slade in 2015 that he and his band mates likely got the lyrics and melody from Lomax’s book.

Though they had continued to ship each other Christmas gifts over the years — clothes and toys for the Proffitts and a country ham for the Warners — their correspondence increased in the aftermath of “Tom Dooley.” Their letters, many of which are stored at the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Duke University, exude reverence and warmth.

“It is a fine thing that recent happenings have stimulated your re-interest in your people’s songs. You have a very unusual understanding of their value as part of the American heritage. Remember our talks about this way back in 1940? I felt then that you understood better than almost anyone that I had sung with why it is so important to get these songs down,” Warner wrote Proffitt in September 1959. He then added: “I hope that tobacco crop comes out better than it seemed at first.”

Though a phonetic speller, Proffitt was a prolific letter writer, documenting life on the farm with subtle humor and occasional poetic flairs.

In November 1959, he sent Warner a three-page essay, “Memories of Tom Dooley.”

“I had a happy suprise one day when I met Frank and Anne Warner of New York and they made me understand that the songs that have come down for years and years even from father to son and mother to daughter was rich in historical value. Through them I learned that the mountain folk had nothing to be ashamed of although many was unlearned through no fault of their own.”

A Warner family visit to Pick Britches Valley (now known as Mountain Dale) in the summer of 1959 also re-invigorated their friendship.

Ed Proffitt remembers seeing the Warners and their two boys, Jeff and Gerret, drive up to their house in a 1957 Ford Ranch Wagon trimmed in wood grain.

For the Proffitt kids, who spent summers picking beans and strawberries, their arrival was cause for celebration.

“This was a week away from that, and believe you me, that was a week of festivities,” recalled Ed Proffitt. He and his brothers scampered in creeks and shot rifles with the Warner boys while neighbors and family gathered on the Proffitt porch to play music. “The music was continual for a week,” Ed Proffitt said.

The “Tom Dooley” lawsuit was eventually settled out of court, with Lomax and Warner sharing royalties generated from the song after 1962, long after the song’s peak. The Warners agreed to split their 50-percent share with the Proffitts, a handshake agreement that continues to this day.

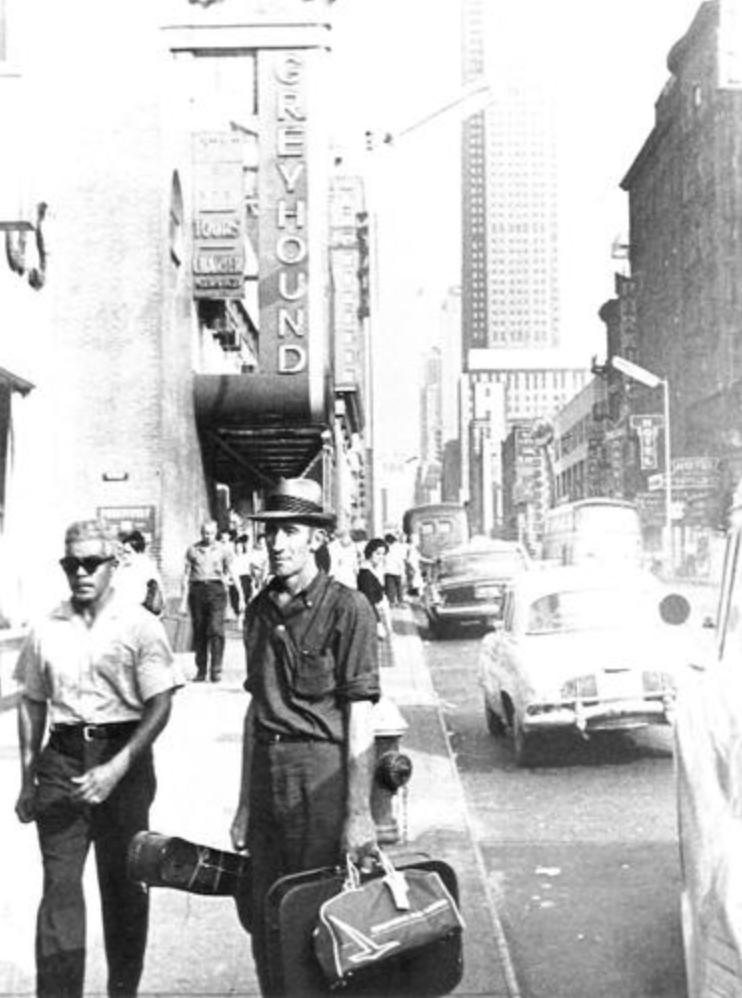

The folk boom that “Tom Dooley” set off meant more people wanted to hear authentic voices from the mountains. Warner persuaded the reluctant Proffitt to join him at a folk festival at the University of Chicago in 1961 that featured Willie Dixon, Memphis Slim and The Stanley Brothers.

A few months later, Proffitt was Warner’s guest at a folk music camp in Massachusetts. In one photo, a group of campers are circled around Proffitt studying his hands on a dulcimer.

The mountaineer who once imagined life beyond Pick Valley Britches was now out in the world, playing concerts — as long as they didn’t interfere with his farm work — and sitting for interviews with Time and Life.

“I hope I can handle it all and remain my own true self, a thing I will seek to do with all my heart,” Proffitt wrote Warner.

In 1964, Proffitt played two big shows, the New York World’s Fair and the Newport Folk Festival in Rhode Island. Footage from that festival shows Proffitt sitting in a chair, a fretless banjo on his knee. “This music was never meant to be played, I suppose, to such a large crowd because a banjo like this is meant to be played in a cabin in my mountain country,” Proffitt explained to about 1,000 college kids sitting around him.

The extra income helped pull Proffitts out of poverty. Prior to “Tom Dooley,” Proffitt had written to Warner that his family was in “pretty desperate condition. Anything that helps will seem like a divine gift.”

On Nov. 22, 1965, Proffitt died in his sleep at a new home he had built, not far from his old cabin, at the age of 52. His death merited a two-column obituary in The New York Times.

Proffitt is buried on a knoll next to a Christmas tree farm, deep in the mountains that gave him songs about moonshining, heartbreak, hardships and groundhog gravy.

Warner continued to trumpet the songs of Frank Proffitt until his death in 1978.

“We got to be blood brothers, really,” Warner told folk music legend Pete Seeger during a TV show devoted to Proffitt’s music.

As their parents undoubtedly would have wanted, the Proffitts and Warners continue to keep in touch.

“You know how you have those deep and abiding friendships even though you may not see them for awhile? That’s how it is with the Proffitts. We’re miles away, leading very different lives, but we feel a real kinship. I guess because of our parents,” Gerret Warner said, “and also the music.”

The gift of music

The Kingston Trio’s recording of “Tom Dooley” sold 6 million copies and earned a Grammy Award for Best Country & Western Performance in 1959. In addition, the Grammy Awards inducted the Trio’s version of the song into its Hall of Fame in 1998, and in 2008, it joined the Library of Congress’s National Recordings Registry, which honors significant recordings in American history.

Frank Proffitt made banjos and dulcimers that are valued by collectors around the world; he sang in a warm voice and was a proficient multi-instrumentalist. But his greatest gift may have been his willingness to share the songs he learned as a piney knot burned in a cabin stove.

“He doesn’t have that claim on our attention because of the greatness of his performances,” music critic Greil Marcus said. “He was a carrier, and he helped carry that song to the point where we are talking about it.”